Picture this: Me, running around Kansas City in a mad dash, a list of a dozen or so books in my hand, trying to complete all my errands and find the titles of my required reading before I left for Indy that weekend. Having visited my local second-hand book store and Half-Priced Books, I had only knocked about three off the list, so I grudgingly (read: happily) went into my third bookstore of the day and turned out my pockets. After a thorough search I found a couple more (each of them the last remaining in-store copy) nestled in the shelves, and completed a final sweep, eager to check everything off my list. Maybe it was the repetitive wandering, could have been the desperate look in my eyes, but after a few minutes of this, I was approached by a Barnes and Noble clerk.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“I’m looking for copies of these books,” I flashed my half-found list at him.

“Let’s see what we can do.”

He grabbed my notebook and took it to his fancy “employees only” station, narrating all the titles to me, confirming that no, none of the remaining books were in store, but I could find them online.

Listen, bud. I didn’t want to turn to the big, bad ‘net. I wanted physical copies in my stressed out, overeager hands. I needed them for class, and I told him so, using it as a convenient excuse to go find the books somewhere else, rather than have him order them right then and there.

“You need these for class?”

I just blinked at him and nodded. After all, that was what I had just told him.

“A college professor told you to get these?”

I looked down at the list of books in front of me, the source of his confusion.

“Yes. It’s a young adult lit class.”

He chuckled and handed my list back to me, in seeming disbelief.

“Hey buddy, you’re allowed to study authors other than Hemingway in college, okay?” I said. Well, I didn’t, but it echoed around my head.

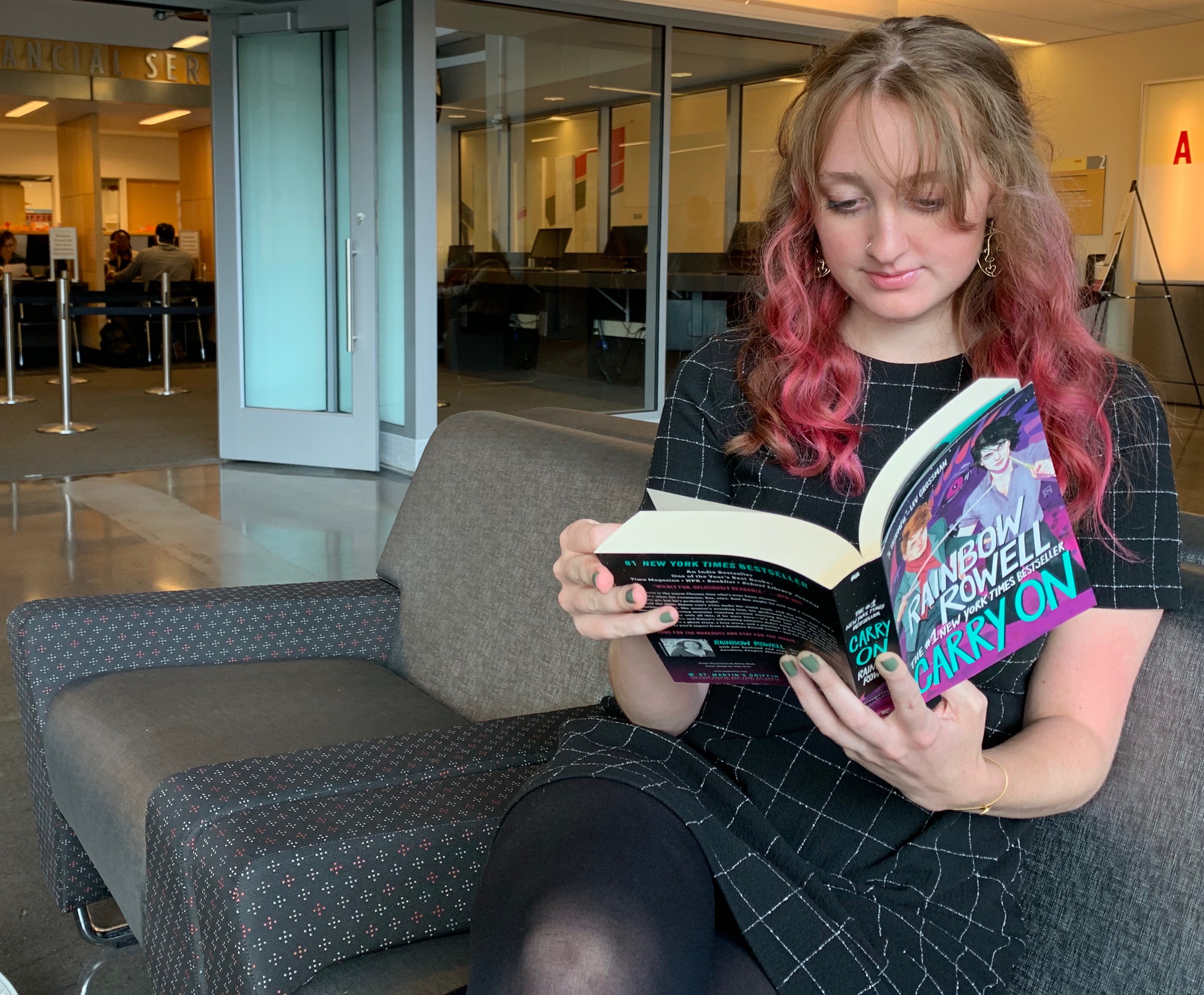

This reaction to young adult literature is not a new one. When you bring a list of books in for a college class, they’re supposed to be daunting and obviously hard to crack, novels from the classics section that most people would only pick up when explicitly directed to by a professor. They’re not supposed to have colorful covers and adolescent protagonists. Why? Because oftentimes, young adult literature is labeled fundamentally uncomplicated, meaning it wouldn’t be worth the time spent studying it in a collegiate setting. In recent cultural debates, critic Ruth Graham champions this idea, lamenting the decline of intellectualism in adult readership due to the replacement of literary fiction with young adult literature. Her claim: if adults have a copy of a young adult book in their hands, they should feel embarrassed.

“[Readers] are asked to abandon the mature insights into that perspective that they (supposedly) have acquired as adults… even the myriad defenders of YA fiction admit that the enjoyment of reading this stuff has to do with escapism, instant gratification, and nostalgia.” (Graham, 2014).

My local Barnes and Noble clerk had taken an obvious stance on Graham’s side. From a personal standpoint, I don’t care – I’m resilient and can take the haters. But in the broader scheme of things, why do people over the age of eighteen continue to read literature that is apparently written only for adolescents? Why does my institution have a course devoted to these types of works? Because contrary to Graham’s beliefs, young adult literature is far from being unsophisticated.

To take an example from the class reading list: Angie Thomas’s The Hate U Give tells the story of a young girl who is with her friend when he’s murdered as a result of police brutality, and subsequently must deal with issues of race-relations in America, institutionalized racism, dehumanization of both herself and those in the community around her, class conflicts, self-identity, and more. This book is a window into the very real realities of modern America; nothing about the content of this book speaks “escapism, instant gratification, and nostalgia.” Rather, the realities of the story pose difficult questions about the world that has been constructed around us and forces the reader to think about how they operate in a society in which these are the realities. Critic Damien Walter points out that this is true of many YA books:

"Increasingly the evil in young adult fiction is the adult world itself. In TheHunger Games it’s an adult world of political and economic repression. In Divergent it’s an adult world that demands conformity, at the expense of the individual. In The Maze Runner it’s an adult world that has escalated to such technological complexity that we are all lost within it. And increasingly, it’s not just teenagers that need allegorical warnings against adult reality, but adults themselves… Is it possible that young adult novels are supremely popular not because we are a culture of infantilised idiots, but because they are the best guide we have to the dysfunctional reality of adult life?" (Walter, 2014).

Whether we’re talking about the mundanity of day to day life, or larger social issues, young adult literature can provide a useful guide. Carrie, by Stephen King, examines the reactions of adolescents at the hands of cruelty. Samuel Miller’s A Lite Too Bright delves into the importance of mental health for teens and adults alike. Six of Crows examines the worth of an individual beyond their label in society. The graphic novel Nimona presents critiques of today’s gender roles.

Does every young adult novel have something as powerful to say as this short list of examples? Of course not. But not every novel published for adults is ground-breaking either. Instead of looking at the umbrella the book was marketed under, we need to focus on the content of the work itself, and if it helps us understand our increasingly insensible world, even just a little bit, why would we discount it?